🤺Who Will Fill Nvidia’s AI Chip Void in China?

China pushes Nvidia out while homegrown players race to prove they can power the country’s AI future.

For more than a decade, Nvidia’s chips have been the beating heart of China’s AI ecosystem. Its GPUs powered search engines, video apps, smartphones, electric vehicles, and the current wave of generative AI models. Even as Washington tightened export rules of advanced AI chips, Chinese companies kept settling for and buying “China-only” versions stripped of their most advanced chips—H800, A800, and H20.

But by 2025, patience in Beijing had seemingly snapped. State media began labeling Nvidia’s China-compliant H20 as unsafe and possibly compromised with hidden “backdoors.” Regulators summoned company executives for questioning, while reports from Financial Times surfaced that tech companies like Alibaba and ByteDance were quietly told to cancel new Nvidia GPU orders. Chinese AI startup DeepSeek also signaled in August that its next model will be designed to run on China’s “next-generation” domestic AI chips.

The message was clear: China could no longer bet its AI future on an U.S. supplier. If Nvidia won’t—or can’t—sell its best hardware here, domestic alternatives must fill the void.

That’s difficult, some say it’s impossible. Nvidia’s chips set the global benchmark for AI computing power. Matching them requires not just raw silicon performance but memory, interconnection bandwidth, software ecosystems, and above all, production capacity at scale.

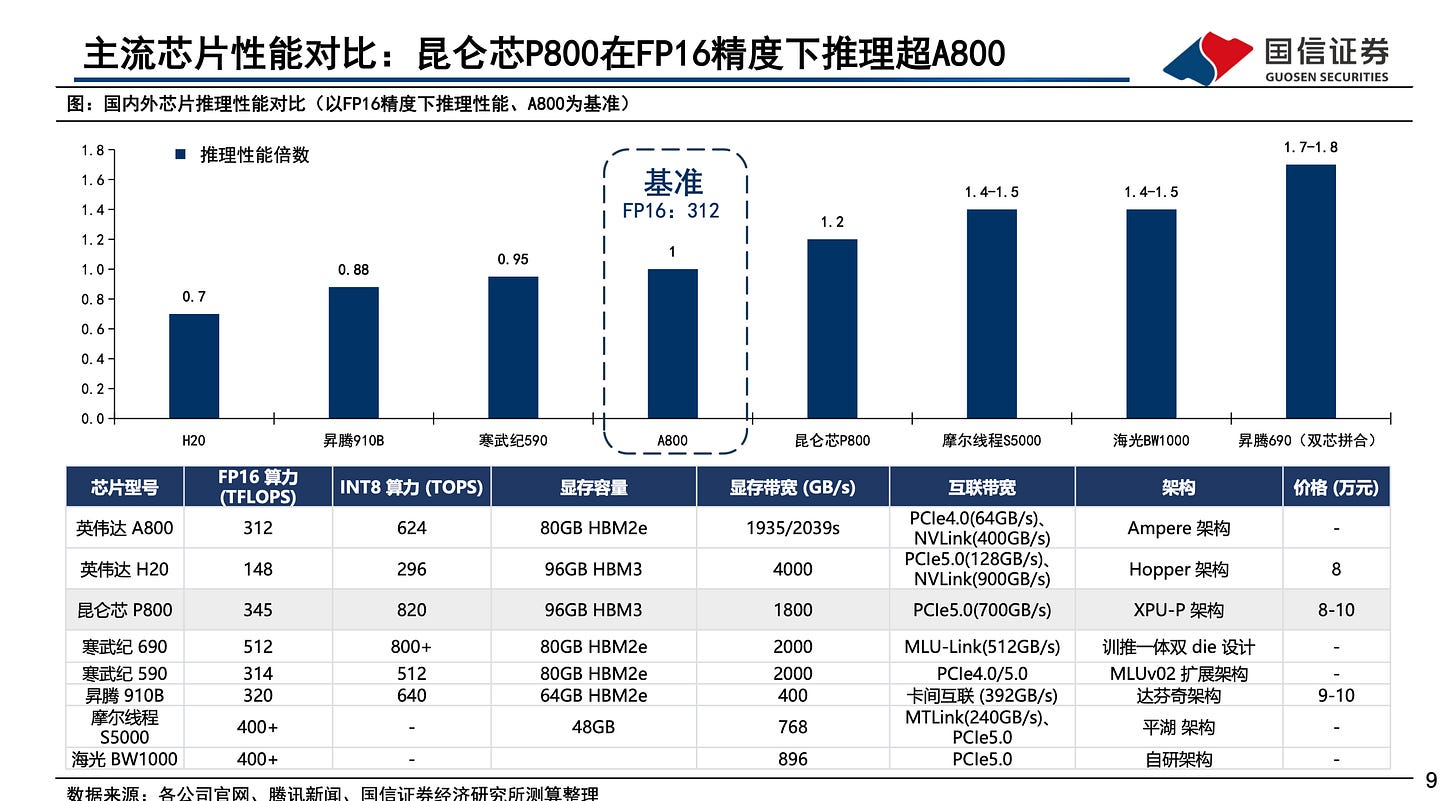

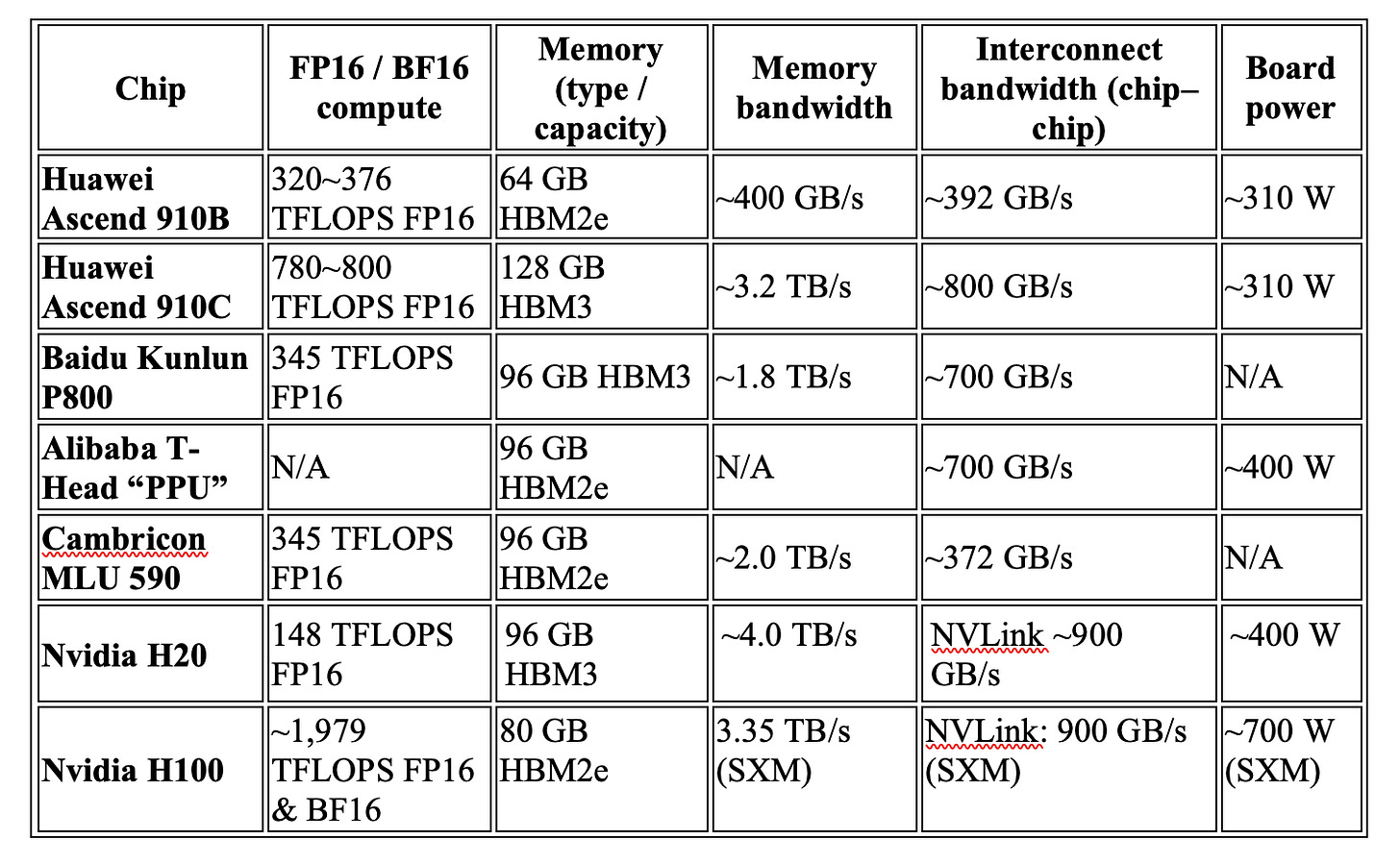

Still, a few contenders have emerged as China’s best hope: Huawei, Alibaba, Baidu, and Cambricon. Each tells a different story about China’s bid to reinvent its AI hardware stack. (Below is a chart comparing leading publicly available domestic AI chips with Nvidia’s H100 and H20.)

Huawei: The Favorite

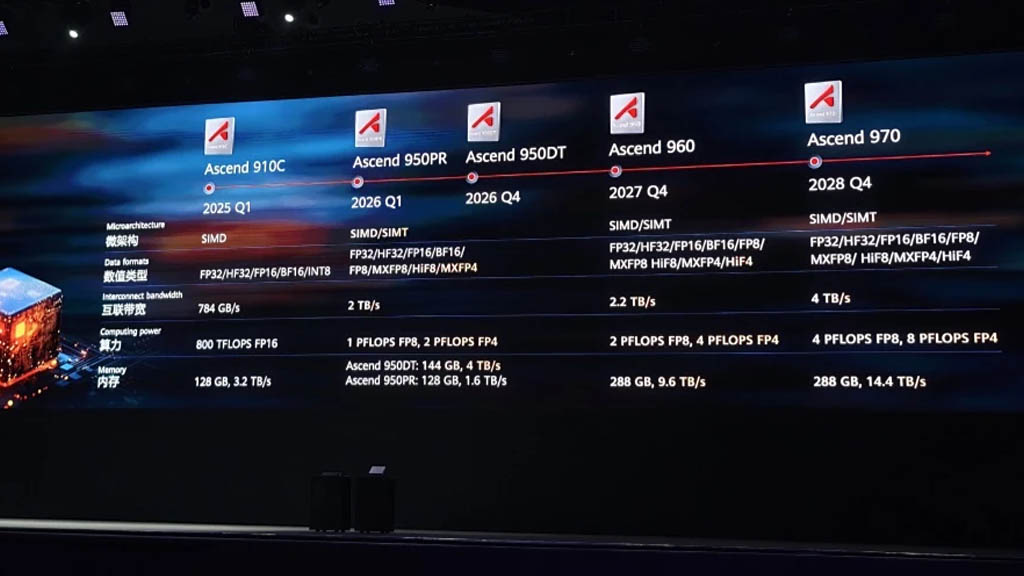

If Nvidia is out, Huawei looks like the natural replacement. Its Ascend line of AI chips has matured under the U.S. sanctions, and for the first time the company in September 2025 has laid out a multi-year public roadmap:

Ascend 950, expected in 2026 with performance targets of 1 PFLOPS at FP8, 128–144 GB of memory and interconnect bandwidths up to 2.0 TB/s.

Ascend 960 in 2027 is projected to double the 950’s capabilities

Ascend 970 is further down the line, each promising significant leaps in both compute power and memory bandwidth.

The current offering is the Ascend 910B, introduced after U.S. sanctions cut Huawei off from global suppliers. Roughly comparable to Nvidia’s 2020 state-of-the-art A100, it became the de facto option for companies who couldn’t get Nvidia’s GPUs. One Huawei official even claimed the 910B outperformed the A100 by around 20% in some training tasks in 2024. But the chip still relies on older HBM2E memory, leaving it short of Nvidia’s H20 in memory capacity by one-third and chip-to-chip bandwidth by 40%. .

The company’s latest answer is the 910C, a dual-chiplet design that fuses two 910Bs. In theory it can approach the performance of Nvidia’s H100—Huawei itself showcased a 384-chip Atlas 900 A3 SuperPoD cluster that reached roughly 300 PFLOPS of compute, implying each 910C can deliver just under 800 teraflops at FP16. That’s still shy of the H100’s ~2,000, but enough to train large-scale models if deployed at scale. In fact, Huawei detailed how they used Ascend AI chips to train DeepSeek-like models.

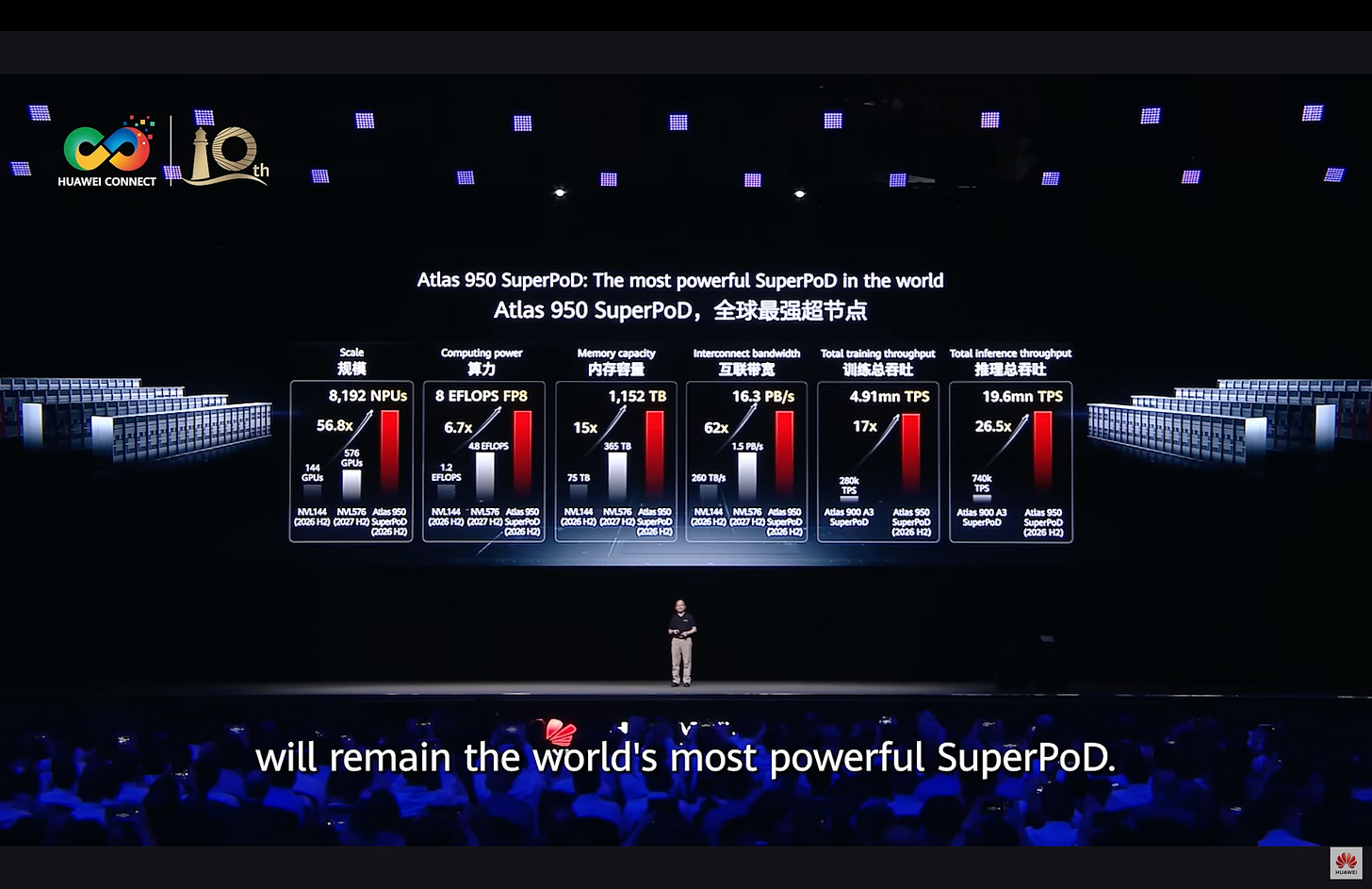

To address the performance gap at the single-chip level, Huawei is betting on rack-scale supercomputing clusters that pool thousands of chips together for massive gains in computing power. Building on its Atlas 900 A3 SuperPoD, the company plans to launch the Atlas 950 SuperPoD in 2026, linking 8,192 Ascend chips to deliver 8 EFLOPS of FP8 performance, backed by 1,152 TB of memory and 16.3 PB/s of interconnect bandwidth. The cluster will span a footprint larger than two full basketball courts. Looking further ahead, Huawei’s Atlas 960 SuperPoD is set to scale up to 15,488 Ascend chips.

Hardware isn’t Huawei’s only play. Its MindSpore deep learning framework and lower-level CANN software are designed to lock customers into its ecosystem, offering a domestic alternative to PyTorch and CUDA respectively.

State-backed firms and U.S.-sanctioned companies like iFlytek, 360, and SenseTime have already signed on as clients. Chinese tech giants such as ByteDance and Baidu also ordered a small batch of chips for trial.

Yet Huawei isn’t an automatic winner. Chinese telecom operators such as China Mobile and Unicom, which are also responsible for building China’s data centers, remain wary of Huawei’s influence. They often prefer to mix GPUs and AI chips from different suppliers rather than fully commit to Huawei. Big internet platforms, meanwhile, worry that partnering too closely could hand Huawei leverage over their own intellectual property.

But even so, Huawei is better positioned than ever to take on Nvidia.

Alibaba: From Cloud to Chips

Alibaba’s chip unit, T-Head, was founded in 2018 with modest ambitions around RISC-V processors and data center servers. Today, it’s emerging as one of China’s most aggressive bids to compete with Nvidia.

T-Head’s first AI chip is Hanguang 800 chip, an efficient inference chip announced in 2019 able to process 78,000 images per second and optimize recommendation algorithms and LLMs. Built on a 12-nanometer process with around 17 billion transistors, the chip can deliver up to 820 TOPS of peak performance and around 512 GB/s memory bandwidth.

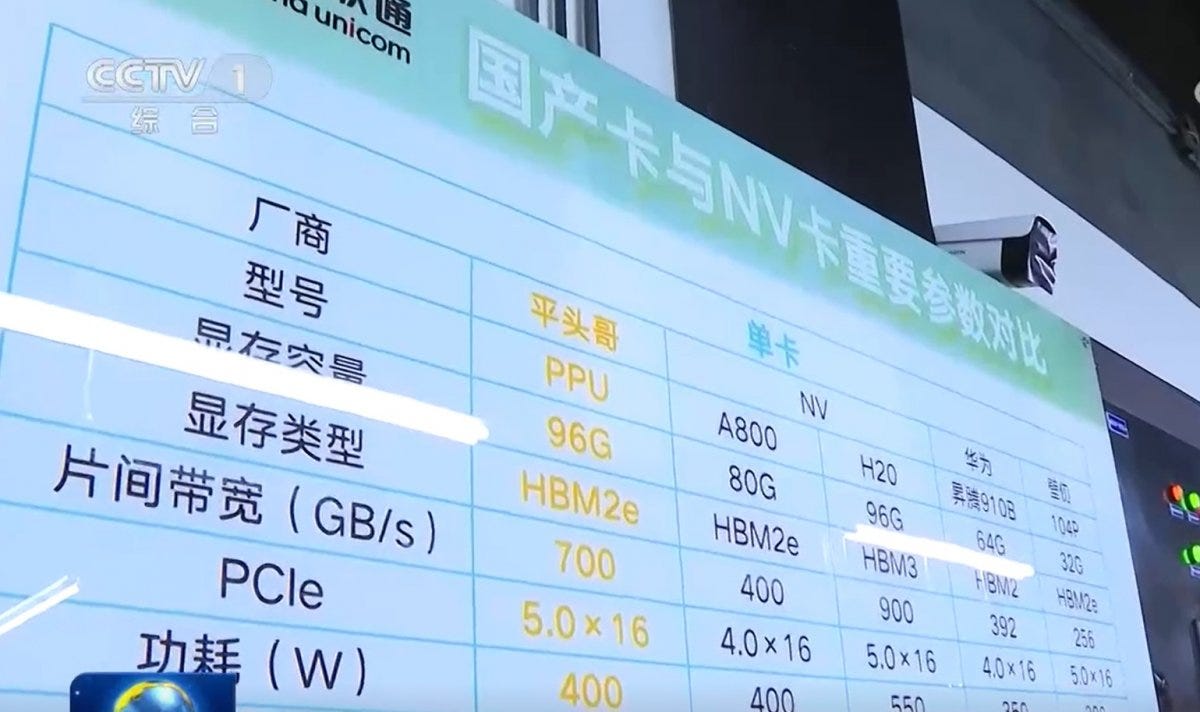

But its latest design—the so-called “PPU”—is something else entirely. Built with 96 GB of high-bandwidth memory and PCIe 5.0 support, the PPU is pitched as a direct rival to Nvidia’s H20.

At a state-backed Television program featuring a China Unicom data center, the PPU was presented as capable of rivaling Nvidia’s H20. Reports suggest this data center runs over 16,000 PPUs out of 22,000 chips in total. The Information also reported that Alibaba has been using its AI chips to train LLMs.

Besides chips, Alibaba Cloud lately also upgraded its supernode server, named Panjiu, featuring 128 AI chips per rack, modular design for easy upgrades, and full liquid cooling.

For Alibaba, the motivation is as much about cloud dominance as national policy. Its Alibaba Cloud business depends on reliable access to training-grade chips. By making its own silicon competitive with Nvidia’s, Alibaba keeps its infrastructure roadmap under its own control.

Baidu: Betting Big on Kunlun

Baidu’s chip story began long before today’s AI frenzy. As early as 2011, the search giant was experimenting with FPGAs to accelerate its deep learning workloads for search and advertising. That internal project later grew into Kunlun.

The first generation arrived in 2018. Kunlun 1 was built on Samsung’s 14nm process, and delivered around 260 TOPS with a peak memory bandwidth of 512 GB/s. Three years later came Kunlun 2, a modest upgrade. Fabricated on a 7nm node, it pushed performance to 256 TOPS for INT8 and 128 TFLOPS for FP16, all while reducing power to about 120 watts. Baidu aimed this second generation less at training and more at inference-heavy tasks such as Apollo autonomous cars and Baidu AI Cloud services. Later this year, Baidu spun off Kunlun into a new, independent company called Kunlunxin at a then valuation of $2 billion.

For years, little surfaced about Kunlun’s progress. But that changed dramatically in 2025. At its developer conference, Baidu unveiled a 30,000-chip cluster powered by its third-generation P800 processors. Each P800 chip, according to research by Guosen Securities, reaches roughly 345 teraflops at FP16, putting it in the same level as Huawei’s 910B and Nvidia’s A100. Its interconnect bandwidth is reportedly close to Nvidia’s H20. Baidu pitched the system as capable of training “DeepSeek-like” models with hundreds of billions of parameters. Baidu’s latest multimodal models, Qianfan-VL with 3 billion, 8 billion, and 70 billion parameters, were all trained on its Kunlun P800 chips.

Kunlun’s ambitions extend beyond Baidu’s internal demands. This year, Kunlun chips had secured orders worth over 1 billion yuan (~$139 million) for China Mobile’s AI projects. That news helped restore investor confidence: Baidu’s stock is up 64% this year, with the Kunlun reveal playing a central role.

Still, challenges loom. Samsung has been Baidu’s foundry partner from day one, producing Kunlun chips on advanced process nodes. Yet reports from Seoul suggest Samsung has paused production of Baidu’s 4nm designs.

Cambricon: Make the Comeback

Cambricon is probably the best performing publicly-trade company on China’s domestic stock market. Over the past 12 months, Cambricon’s share price has jumped nearly 500%.

The company was officially spun out of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2016, but its roots stretch back to a 2008 research program focused on brain-inspired processors for deep learning. By the mid-2010s, the founders believed AI-specific chips were the future.

In its early years, Cambricon focused on NPUs for both mobile devices and servers. Huawei was a crucial first customer, licensing Cambricon’s designs for its Kirin mobile processors. But as Huawei pivoted to develop its own chips, Cambricon lost a flagship partner, forcing it to expand quickly into edge and cloud accelerators. Backing from Alibaba, Lenovo, iFlytek, and major state-linked funds helped push Cambricon’s valuation to $2.5 billion by 2018 and eventually landing it on Shanghai’s Nasdaq-like STAR Market in 2020.

The next few years were rough. Revenues fell, investors pulled back, and the company bled cash while struggling to keep up with Nvidia’s breakneck pace. For a while, Cambricon looked like another cautionary tale of Chinese semiconductor ambition. But by late 2024, fortunes began to change. The company returned to profitability, thanks in large part to its newest MLU series of chips.

That product line has steadily matured. The MLU 290, built on a 7nm process with 46 billion transistors, was designed for hybrid training and inference tasks, with interconnect technology that could scale to clusters of more than 1,000 chips. The follow-up MLU 370, the last version before Cambricon’s being sanctioned by the U.S., can reach 96 TFLOPS at FP16.

The real deal came with the MLU 590 in 2023. The 590 was built on 7nm and delivered perk performance of 345 TFLOPS at FP16, with some reports suggesting it could even surpass Nvidia’s H20 in certain scenarios. Importantly, it introduced support for less-precision data formats like FP8, which eased memory bandwidth pressure and boosted efficiency. This chip didn’t just mark a leap—it turned Cambricon’s finances around, restoring confidence that the company could deliver commercially viable products.

Now all eyes are on the MLU 690, currently in development. Industry chatter suggests it could approach, or even rival, Nvidia’s H100 in some metrics. Expected upgrades include denser compute cores, stronger memory bandwidth, and further refinements in FP8 support. If successful, it would catapult Cambricon from “domestic alternative” status to a genuine competitor at the global frontier.

Cambricon still faces hurdles: its chips aren’t yet produced at the same scale as Huawei’s or Alibaba’s, and past instability makes buyers cautious. But symbolically, its comeback matters. Once dismissed as a struggling startup, Cambricon is now seen as proof that China’s domestic chip path can yield profitable, high-performance products.

A Geopolitical Tug-of-War

At its core, the battle over Nvidia’s place in China isn’t really about teraflops or bandwidth. It’s about control. Washington sees chip restrictions as a way to protect national security and slow Beijing’s advance in AI. Beijing sees rejecting Nvidia as a way to reduce strategic vulnerability, even if it means temporarily living with less powerful hardware.

China’s big four contenders, Huawei, Alibaba, Baidu, and Cambricon, along with other smaller players such as Biren, Muxi, and Suiyuan, don’t yet offer the best substitutes. Most of their offerings are barely comparable with A100, Nvidia’s best chips five years ago, and they are still on their way to catch up with H100, which was available three years ago.

Each player is also bundling its chips with proprietary software and stacks, which could force Chinese developers accustomed to Nvidia’s CUDA to spend more time adapting their AI models and, in turn, could affect both training and inference.

DeepSeek’s development of its next AI model, for example, has reportedly been delayed. The primary reason appears to be the company’s effort to run more of its AI training or inference on Huawei’s chips.

The question is not whether China can build chips—it clearly can. The question is whether and when it can match Nvidia’s combination of performance, software support, and trust from end-users. On that front, the jury’s still out.

But one thing is certain: China no longer wants to play second fiddle in the world’s most important technology race.